Caesar and Vercingetorix

£5.00

The dramatic painting by L.Royer depicting Vercingetorix’s surrender to Julius Caesar (shown above) provided Gary with some great inspiration for this piece, which sees the once proud Gallic leader reduced to the role of prisoner.

When Julius Caesar sat on his makeshift throne to take the surrender of the Gallic chief Vercingetorix in October 52 BC, he may have reflected on what a long road it had been to finally defeat the proud Gauls. Vercingetorix, kneeling at Caesar’s feet in subjugation, must have wished he had never set eyes on the Roman commander and his all-conquering legions.

The journey to this moment began in 59 BC when Caesar completed his Consulship in Rome and engineered his appointment to the governorship of the two provinces that constituted Gaul. Moreover, he was given the job for ten years instead of the usual one. That gave Caesar more than ample time to expand the Roman Empire deep into the recesses of northern Europe and even to the shores of Britain. The vast majority of Gauls, of course, did not foresee their destiny in quite the same way.

Caesar used the by-now traditional Roman method of expanding their Empire; diplomacy backed by the sword. He crushed tribes who opposed him and he used those victories to cow others into surrendering their freedom for peace. However, it was not all plain sailing for the Roman military genius. His conquests produced political opposition in Rome that attempted to bring him to heel. Also, any Gallic victory could put a severe

The situation deteriorated rapidly for the thousands of Gauls inside Alesia. Rather than face starvation, they expelled the women and children, believing Caesar would allow them through the walls. They were wrong; Caesar blocked all escape and the Gallic warriors had to watch as their families starved between the lines. Hope finally arrived for Vercingetorix at this moment of crisis dent in Caesar’s ambitions. Such was the case in 53 BC when the Eburones ambushed and annihilated Caesar’s 14th Legion, prompting the rest of Gaul to rise in revolt. The united Gallic tribes then appointed Vercingetorix to lead their fight and massacred Roman colonists throughout Gaul.

A thoroughly alarmed Caesar marched immediately into Central Gaul, seizing the strategic initiative. He next split his army, sending half north while he chased Vercingetorix with his remaining five legions and his auxiliary cavalry. At first, Caesar bit off more than he could chew by attacking Vercingetorix at Gergovia and he retreated precipitously with severe losses. More fighting followed in the forests and valleys of Gaul, but Vercingetorix did not feel that he could take on Caesar’s army in the open with the force he had at his disposal. He opted instead to regroup his forces in the hilltop fort at Alesia. Caesar did not have the strength to assault Alesia head-on, so settled down to besiege the Gauls.

The siege of Alesia stands as a symbol of Roman determination and military proficiency. Within three weeks, Caesar’s legions built an 18km contravallation of Alesia consisting of 12 feet high wooden walls studded with fortlets and watchtowers. A second wall was built, the circumvallation, to complement the inner wall. The soldiers then dug moats and planted mantraps on both sides of the siege walls – it was important not only to keep the Gauls in, but also to prevent relief from coming from the outside. Their work done, the Romans waited within their walls for the Gauls to either surrender or attempt to break out.

The situation deteriorated rapidly for the thousands of Gauls inside Alesia. Rather than face starvation, they expelled the women and children, believing Caesar would allow them through the walls. They were wrong; Caesar blocked all escape and the Gallic warriors had to watch as their families starved between the lines. Hope finally arrived for Vercingetorix at this moment of crisis in the form of a relief force, and the besiegers became besieged.

Vercingetorix ordered a sally from Alesia to coincide with an attack by the relief force. The fighting that ensued lasted all day, but by nightfall, both sides had retired. The Gauls then attacked in darkness, forcing Caesar to surrender part of the walls, but the timely arrival of the Roman cavalry averted complete disaster. The fighting continued. On 2 October, Vercingetorix ordered an all-out attack at every point along the walls, while the relief force advanced once more against Caesar’s fortifications. The Roman legionaries held on desperately and were helped by Roman cavalry dashing around plugging gaps in the lines. Then Caesar, recognizing that his defence could unravel at any moment, commandeered thirteen cohorts of cavalry and launched them against the rear of the Gallic relieving force. The Gauls panicked and fled, pursued by the overjoyed Roman cavalry. Vercingetorix in Alesia saw the route and knew his men could take no more and on 3 October he led his men out to surrender to the Romans. Vercingetorix knelt in front of his conqueror, surrendering his sword and the freedom of the Gauls for the last time.

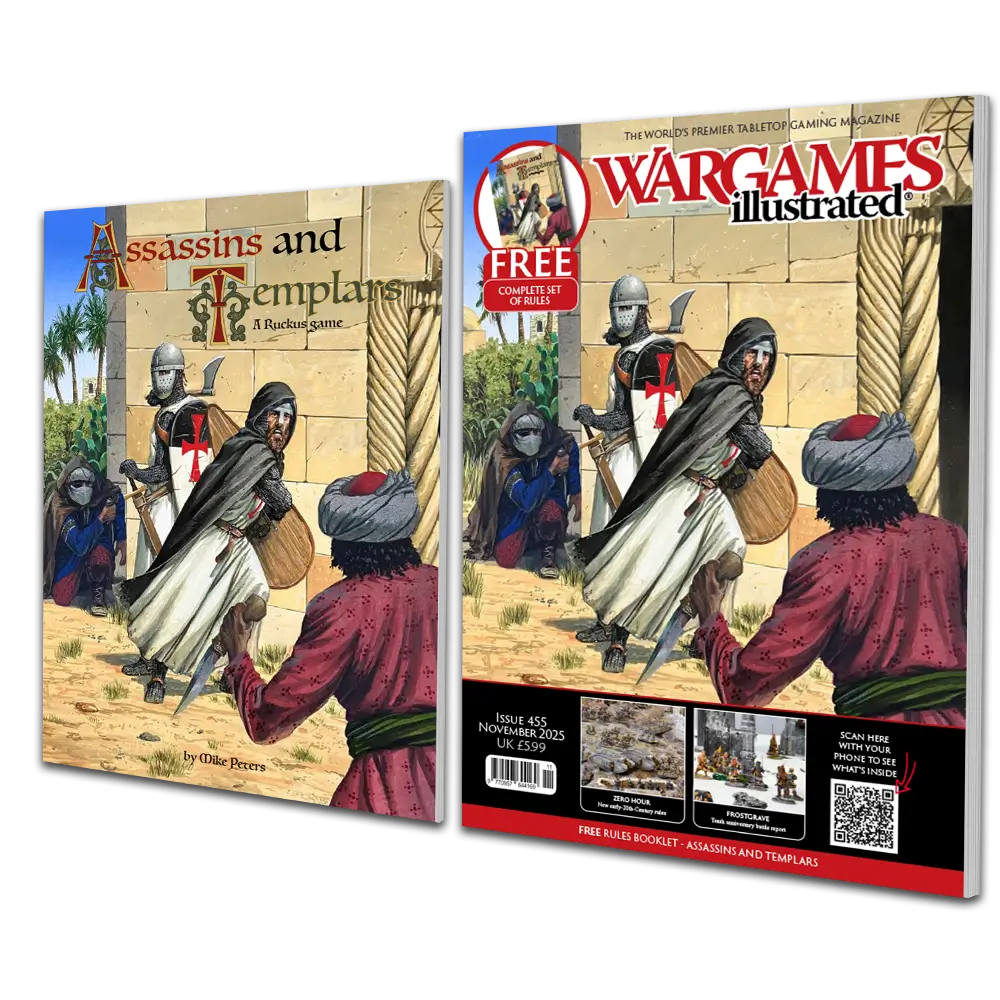

Ordering from outside the UK?

We welcome magazine subscriptions and WiPrime membership orders from outside the United Kingdom – please order via our webstore. Digital/PDF products are also available to purchase and download here.

Our other products: Giants in Miniatures, games, physical magazines, and anything else that requires shipping, should be ordered from our distribution partner North Star Military Figures. You will find all Wi products on their website.

Featured and Discounted Products

Browse the most recent releases in the Wi webstore.