Ordering from outside the UK?

We welcome magazine subscriptions and WiPrime membership orders from outside the United Kingdom – please order via our webstore. Digital/PDF products are also available to purchase and download here.

Our other products: Giants in Miniatures, games, physical magazines, and anything else that requires shipping, should be ordered from our distribution partner North Star Military Figures. You will find all Wi products on their website.

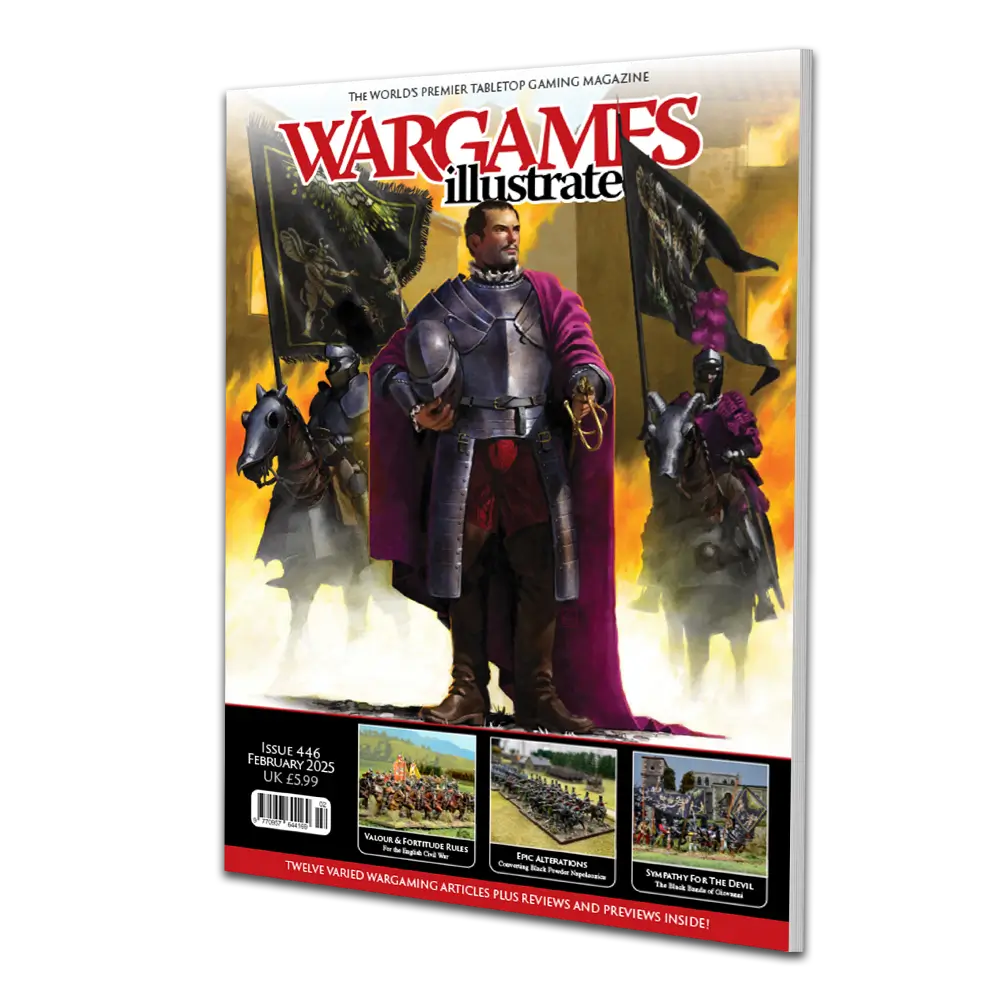

The Eve Of Edgehill

£7.50

Inspiration for this piece came from the famous painting by Charles Landseer in which we see the high command of the Royalist army debating their strategy of the following days battle whilst poring over a map of the field. A great command stand for any English Civil War army.

King Charles I brimmed with confidence on the eve of the first major battle of the English Civil War, 22 October 1642, even though he could still not quite believe that his conflict with Parliament had come to open war. But here they were at Edgehill between Warwick and Oxford, trying to solve the immediate problems of locating the rebel army and what to do when they were found. Charles called together his Lieutenant-General of the Royalist army, Robert Bertie, 1st Earl of Lindsey, and his nephew Prince Rupert, Duke of Batavia. A greater contrast between Lindsey, a steady hand at aged sixty, and the twenty-three years old prince who came to personify the cavalier ideal, could not be found. Moreover, while Charles placed Lindsey in charge of the army, he did not give him command over Rupert. That oversight created a dislocation in command that would almost prove disastrous the following day.

The three men discussed their plans and separated for the evening. They met again very early the next morning to the news that the two armies had literally bumped into each other during the night. The question now was whether or not to stand and fight. Of the three, Charles had the least experience of war. Lindsey fought with Maurice of Nassau, the Dutch Prince of Orange and master military theorist. Rupert too fought for a Prince of Orange, Maurice’s brother Henry, at the age of fourteen. He subsequently fought for the Protestant alliance against the French until his capture at Vlotho in 1638. Lindsey learned Maurice’s Dutch tactical system: Rupert knew how to attack and keep going. Indeed, Rupert felt vindicated when only a week before his cavalry troopers thwarted a Parliamentarian attack on Worcester at the Battle of Powick Bridge. Between them, the Royalist captains decided that now was the time to settle the issue once and for all. There was dissent about how to do that, however, but Rupert’s plea for a swift bold strike against the enemy won out. Lindsey took umbrage and demoted himself to Colonel in command of a regiment.

It took some time for the armies to set up at Edgehill. The two main issues were that the armies had never done this before, and many inexperienced regimental commanders had difficulty rounding up their men. Still, all was in readiness by early afternoon. The Royalist army was 12,000 strong, facing Parliament’s 15,000, not all of whom were on the field. Rupert took charge of the cavalry on the right wing; the infantry formed up in the centre with five regiments in front and four in reserve. Twelve hundred cavalry troopers moved out onto the left wing. At 2pm, the artillery on both sides opened the ball. The shooting lasted an hour; then, the Royalist horse launched their attack on both flanks.

Rupert’s troopers stormed into the Parliamentarian cavalry and sent them reeling to the rear. Orthodox military theory would have had the Royalist cavalry return immediately to the field, but Rupert’s men were nothing if not impetuous and maintained their pursuit for nearly four miles. That took them out of the picture just as the infantry were coming to grips. The infantry fighting quickly stalemated with neither imposing its will on the other and no cavalry were around in sufficient numbers to turn the tide of battle. As evening drew on, the exhausted combatants broke off the fight and the battle ended a draw. But not before the unfortunate Lindsey found himself surrounded and cut down; a noble end for a brave man. Rupert would go on to bigger and better things, but he made his reputation as a fearsome foe at Edgehill and the Parliamentarians feared him throughout the war.

Featured and Discounted Products

Browse the most recent releases in the Wi webstore.